The Nolde Debate

Emil Nolde is one of the most important German expressionists. Although he was a member of the Danish NS party, he was denounced by the Nazis as a “degenerate artist” in 1937. But Nolde was a Nazi and an anti-Semite. Here are some film documents that we have collected in recent years.

In 1947, on his 80th birthday, the newsreel of the American occupying power publishes a film about Emil Nolde. The narrator tries to portray Nolde as a positive figure for a new beginning of culture and art in Germany. For a long time, the history of the “Verfehmten” will shape the official image of Nolde in post-war Germany.

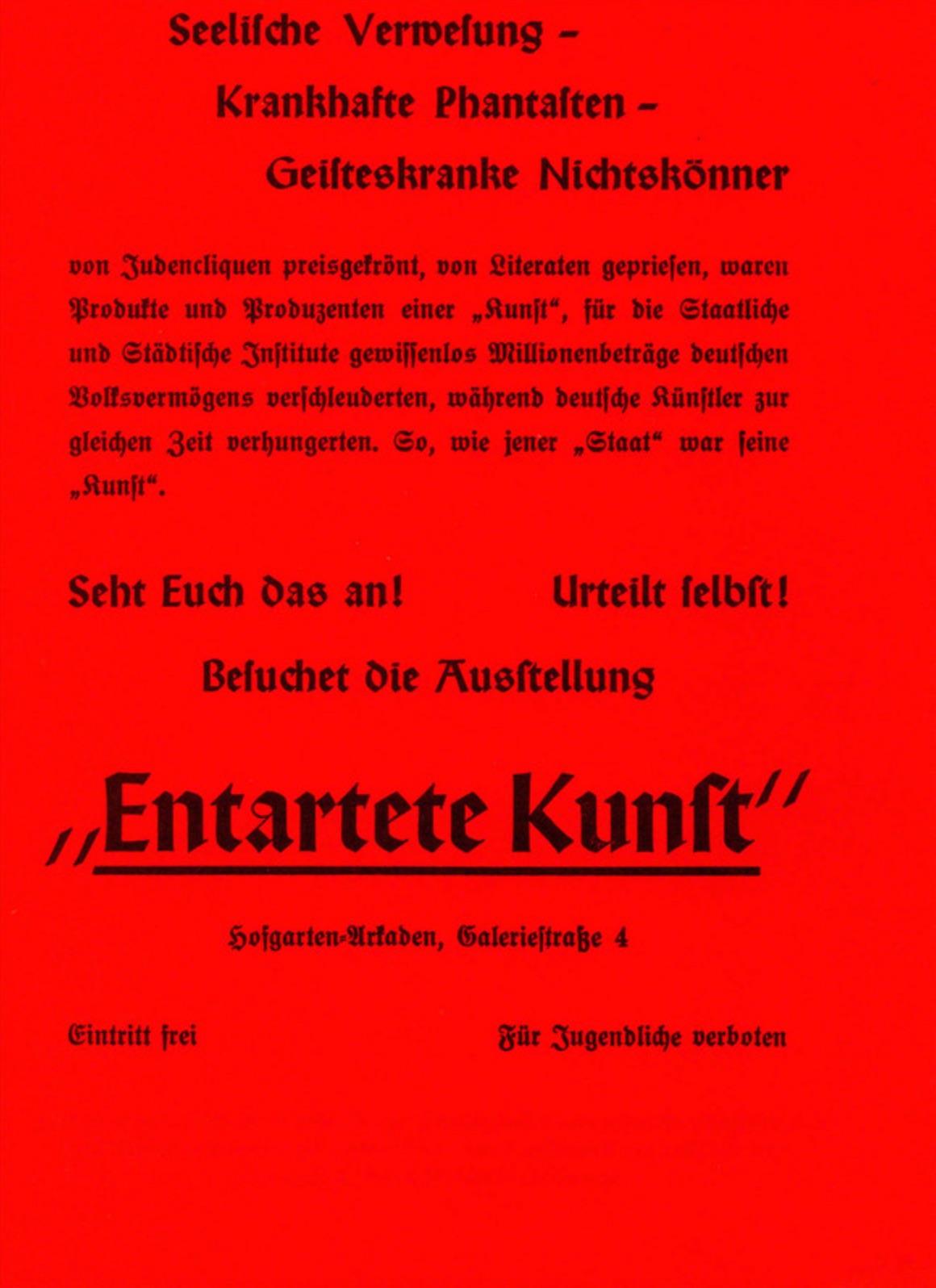

Degenerated art

The “Haus der Deutschen Kunst” was opened in Munich in 1937. The works exhibited there are on a rather simple artistic level, a kitschy realism pleasing to the Führer Hitler. The day before, another picture show was opened in Munich’s Hofgarten. The exhibition “Degenerated Art”. This show reviled almost the entire celebrity of German art in the first half of the 20th century. Here, too, I found a unique film document in the National Archives that the American Julien Bryan shot in Munich in 1937.

The picture marked in the original colours at the end of the film is “Christ and the Sinner” by Emil Nolde. It was acquired by the Berlin National Gallery in 1929. There was a fierce dispute about the recognition of expressionist artists during the Weimar Republic.

Review: The Berlin Secession

Nolde made his first major attempt at recognition in Berlin in 1910. It was fermenting in the art scene, in Munich the Blaue Reiter caused a scandal, in Berlin Nolde and the painters of the “Brücke” also wanted to make a revolution. But Nolde’s paintings were rejected by the Berlin artists’ association Secession. This rejection marks the beginning of Emil Nolde’s history of anti-Semitism. The art dealer Paul Cassirer and the painter Max Liebermann, both Jews, determine the fate of the Secession and become Nolde’s intimate enemies. This personal antagonism was also about Nolde’s threatened economic existence as a free artist.

The recognition

Nolde celebrated his 60th birthday in 1927 and the Kunsthalle Dresden presented him with a large exhibition of his work, which was long overdue for public recognition. Nolde is a very ambitious painter who understands the expressionist style as a unique way of representation. “I would like my paintings to be more than just a nice entertainment by chance, no, that they (…) give the viewer a full sound of life and human existence,” he writes. Since 1927, Nolde has been one of the great stars of classical modernism in Germany. But he remains an anti-Semite and tries to serve himself to the Nazis after 1933. He becomes a member of the Danish NS foreign organization (Nolde is a Danish citizen) and tries to please Hitler by all means. Hans Fehr, perhaps Nolde’s best friend, wrote: “But since everything in Nolde was born out of a primordial instinct, out of a primordial force far from the mind, he saw his innermost being hurt when someone dared to touch this mysterious world”. The deep injury from the years before 1927 perhaps explains the closeness to the Nazis. And Nolde always saw himself as a painter of the Nordic. Nevertheless, Nolde’s art in its radical subjectivity is virtually inconceivable as state art of the Nazi regime.

Unpainted Pictures

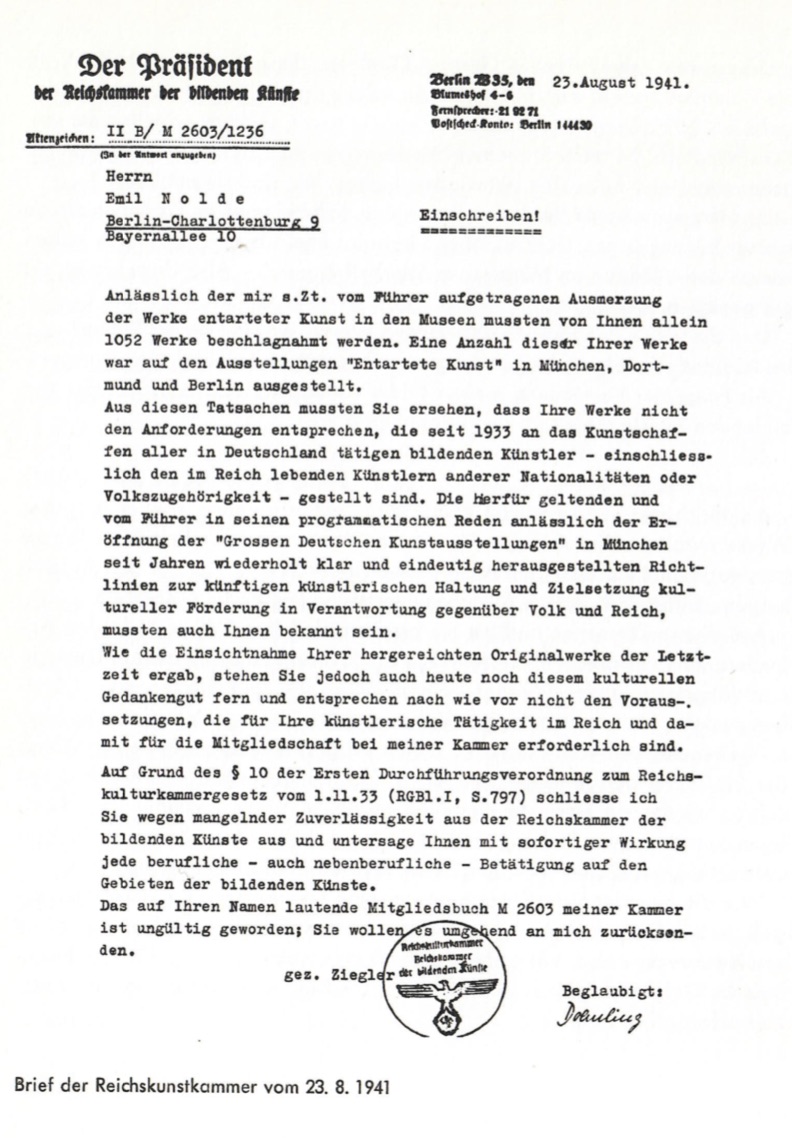

After the blasphemy of 1937, Nolde is banned from selling and painting. 1052 works of art are removed from the museums and a large part are sold for foreign currency to finance the armament. The “distribution and reproduction” of his works was prohibited.

In his letter of 23 August 1941, the President of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, Adolf Ziegler, an artist who is popularly known as the “Master of the German Pubic Hair”, prohibited Emil Nolde “with immediate effect from any occupation, including part-time, in the field of fine arts”. 3 months later the painter was also forbidden to “sell, distribute and reproduce the products listed in the special” (his paintings).

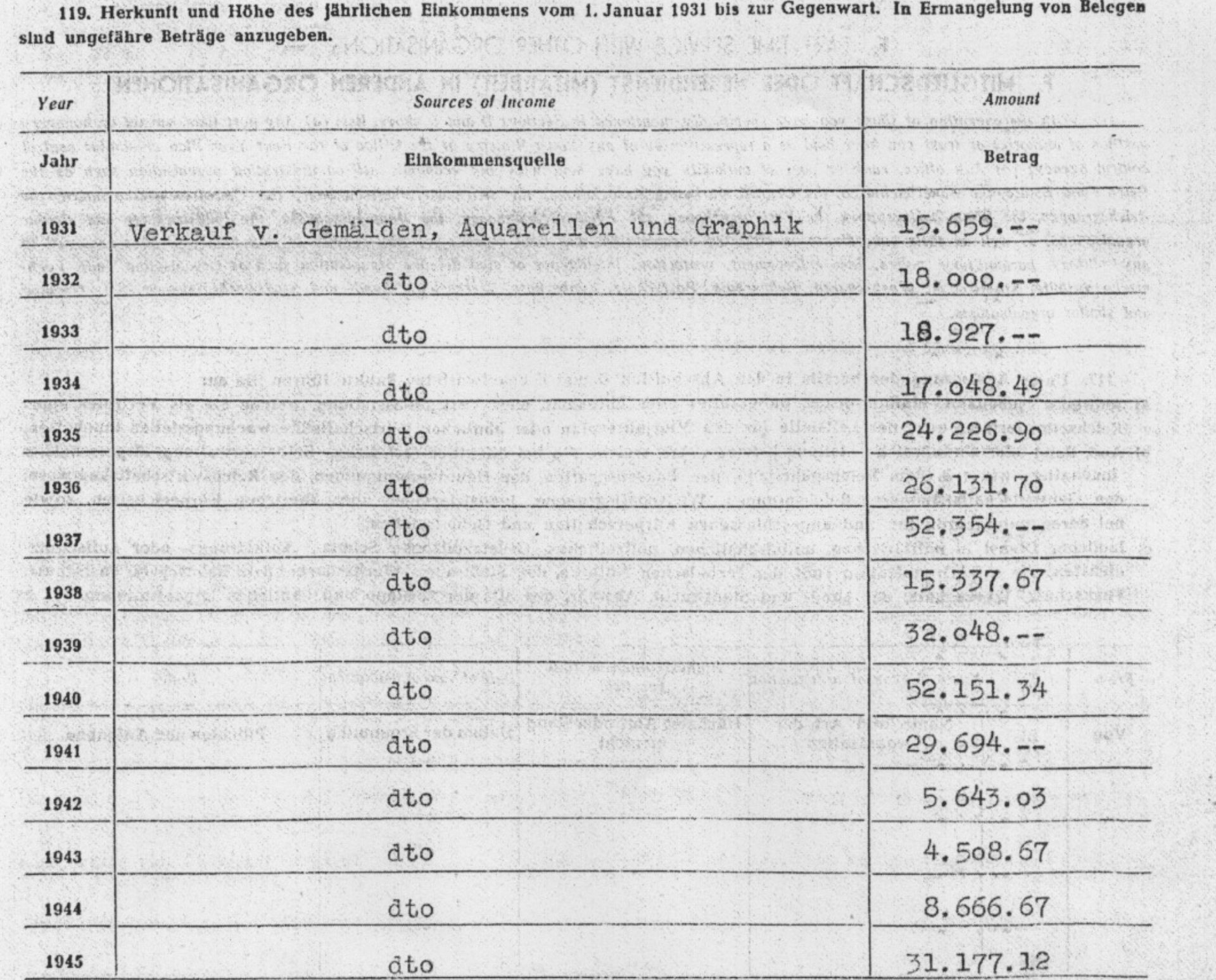

It is objected that the high income from sales in 1940, which Nolde stated in the denazification declaration of 1947, indicates that he had been quite well. It is not said that the income in 1942 was only a tenth of that of 1940. Of course, Nolde, who was over 70 years old at the time, did not have to fear for his life like other persecuted and deprived of his rights. And some private buyers, like 1941 the Hanoverian factory owner Sprengel, supported him with high sums for oil paintings up to the sales prohibition. But the ban on his work brought the great old artist to the brink of despair.

He wrote to Hans Fehr in 1942. “I haven’t worked on anything since the first of August. (…) Not to know what one ‘may’ and ‘may not’ and to have this sword of Damocles hanging over one’s head – does not then the already sensitive artist muse have to leave the people?

New documents prove Nolde’s continuing attempt, even after 1937, to persuade the Nazis to change their minds. The head of the Berlin National Gallery recently announced on television’s evening news that he too (like the Chancellor!) would no longer want to hang Nolde’s in his apartment. A memorably embarrassing statement. It boils down to the same thing the Nazis did with the “degenerate artists”.

The responsibility

The political man Nolde was wrong, but the artist went his way. An artist of Emil Nolde’s rank has a special responsibility for his behaviour. The fact that he was an anti-Semite and that the disenfranchisement and annihilation of his Jewish fellow citizens after 1933 did not lead him to a rethink and a clear break with Nazi ideology has now fortunately been clarified. So there remain questions: Why did moral law fail in him? As one of the most prominent artists of the Weimar period, he had friends among his fellow artists, who had already been driven into emigration in 1933. Among them was Paul Klee, whom he met in Switzerland in 1935. What did the artists discuss? Apparently, as so often, Nolde kept quiet.

Nolde offered himself to the Nazi regime, like Heidegger, Richard Strauss, Gottfried Benn or Mies van der Rohe. They only recognize the populist banality, the plebeian and bloodthirsty violence, and the small-minded taste of the Nazi empire when it’s long too late. They have succumbed to the fascination of evil, when one should expect immunity from them. The French art historian Jean Clair calls this a “humiliation of our moral hierarchies.

Leave A Comment